When I was six, my father would flex his upper arm and ask me to punch it. I punched. It made a pleasing smacking noise.

“Harder,” he would say.

So I would punch harder.

“Harder,” he would say.

And I would hit him with all my might. It didn’t faze him. He was my big, strong father. At that time, I didn’t know that he had been brought up by a mother who was mentally ill, and had an innate inability to display affection. I cringe, thinking about the chaos he grew up in. Hitting each other in the arms was what we did to feel close.

My father was a mesomorph, although his smoking tended to change that over the years. They were a family habit. My mother, who was a skinny young woman, smoked throughout her pregnancy. The doctors recommended it for calming nerves.

When I was five, I liked the odor of tobacco. I had grown up with it. It was inextricably intermingled with the idea of father. But my parents knew it was bad for them, so they promised me a prize of $1,000 if I made it to age 18 and didn’t smoke. He was still a mesomorph and I still hit him in the arm. I took half a puff on a stolen cig at age 13. I stood in front of the bathroom mirror, trying to look cool. But there was always an impenetrable barrier between me and cool, so I never continued. At 18, I put the $1,000 in the bank.

When I went off to college and mingled with people of other cultures, I learned to hug people upon greeting them. Sometimes I even did something unthinkable: Kiss them on the cheek. I started doing that to Dad, and it threw him for a loop.

“When David hugs me,” he once told my mother in private, “I don’t know what to do.”

“Hug him back,” she said.

But something within him made him unable to return the hug. I just kept doing it, though. Hugs never hurt nobody. I figured I was converting him to a new way of being in the world. After a while, he came to expect it, although he never got really comfortable with it.

Later, I learned that he had served in the bloodiest battle of the Korean War, Chosin Reservoir, and had seen hundreds of his buddies slaughtered.

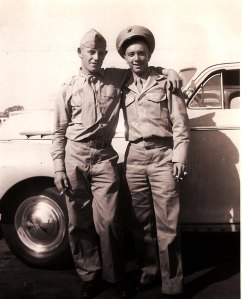

My father in the Marines with his friend Chick, both smoking. His military medical exam showed lung damage even at his early age.

“I learned pretty quickly,” he told my mother when they first got married, “that you don’t make close friends, because as soon as you make a friend, he gets shot dead.”

Maybe that’s what taught him not to hug people, the way he’s doing in the photograph above.

At 29, I would come home occasionally to visit my parents. I was a freelance journalist writing for the likes of American Health, Psychology Today, Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, and the like. Good health was my beat, and I followed all the best health advice. I was so healthy that my sweat smelled like lilacs marinated in noni juice.

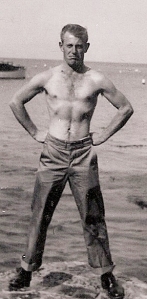

One day, I visited my parents and saw my Dad sitting on the carpeted stairs with his shirt off. The sight shocked me. That wasn’t my father, not the athletic, muscular hero I used to punch in the arm when I was 11.

“Dad, you’ve lost a lot of weight,” I said, trying to quell my rising alarm. “You need to see a doctor.”

His smile suddenly left his face.

“I can take care of it myself.”

“Dad, it’s not normal to lose so much weight. There’s something wrong with you.”

And with that, he got up and walked into his room and closed the door.

I talked with my mother and sister, and we all agreed that he should see a doctor. He had smoked for over 40 years, after all. So my mother promised to “work on him.”

“Leave it to me,” she said.

For four years, my father ignored our impassioned pleas to see a doctor. When we got onto the subject, he would walk out of the room. He would snap at us. He would lock himself in his bedroom.

“I’m taking care of my own health,” he once angrily told us. “I’m listening to Dr. Dean Edell on the radio.”

But I didn’t dare hit my father in the arm anymore. I tried once and he cried out, not playfully, but in real pain.

“Hey!”

He had become too frail.

Then one day, he was dead. In the months that followed, I would suddenly cry at odd moments. In line at the grocery store. Dead at 59. While driving, hearing a lyric on the radio. When you comin’ home dad?/I don’t know when,/But we’ll get together then, son/You know we’ll have a good time then.

“I tried to quit 150,000 times,” he told me on his deathbed.

A few days later, I saw my father walking from the bathroom to the bed, and his paper robe was open in the back. I was shocked. There were no traces of the mesomorph left, nor of basic health. Smoking had withered him down to something I may have seen in news reports about famine.

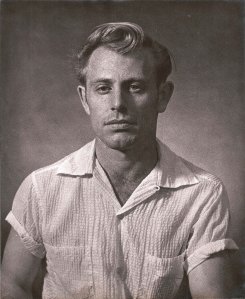

One image of my father remains from my early childhood, and I’m not sure why. I was four years old. We were in the front yard. I was convinced that I had figured out the secret to running fast: All you have to do is move your legs faster than the other boy. Armed with this brilliant insight, I challenged my father to a race. To my astonishment, he creamed me. In my mind’s eye, I see myself running fast, moving my legs like a cartoon. They all told me that young people were our future; that meant me. I was growing stronger every day, and very soon, I would overtake the older generation, I would be dominant, I would be strong. But on that day in my youth, my father was the strong one. Muscular, handsome, swift of foot. I lost that race and he was a god.

My dad too died because of cigarettes. He smoked pall mall with no filters. He died at sixty two. Heart attack. He was not a good guy in fact he was the total opposite of your dad. We did not have a good relationship. When I got married he did not come to the wedding. He hated my wife and my kids. So I surprised my step mother when I showed up at his funeral. She cursed me out but I stayed anyway. I wish my relationship was more on an even keel like you and your dad. Funny I have not one picture of him.

We all have our crosses to bear, some heavier than others.

Thanks for the comment. He has been dead for over twenty years but the scar is there, but since I usually do not pick on it, it stays below the surface. Meanwhile I try my best to go the other way and hug my kids and grandchildren.

I’m truly sorry you lost your father. It sounds like he was such a gift to you. This story touched my heart. Thank you so much for joining me on my blog 🙂

Good to connect. Thanks for the kind words. Please share.

My pleasure. What would you like me to share?

This post, “Hitting My Father in the Arm.” Wherever you like.

To be honest, I envy you. Even though your Father didn’t hug you, he found a way between the two of you to let you know that he loved you, it was his way of showing you affection. That’s amazing given what he went through with his own Father, and I can’t imagine what horror and trauma, he dealt with through war.

My own father is a narcissistic socioapth, very abusive. Our father’s still had choices, your father chose you. That’s a gift.

Yes, I was lucky in many ways. Best to you in surviving your thunderstorm.

Thank you, I’m always happy for those I read about that had loving parents, we see to little of it these days. 🙂

What a wonderful and bittersweet memory of your father. It’s hard to watch your parents grow older. When I was younger, my father was the biggest macho man I knew. My earliest image of him is breaking a pool cue with his bare hands to stop a bar fight. Now, time and cigarettes have turned him into a much older and frailer man. But I think it’s great to remember them in both capacities 🙂